|

| GemHunter looks for gold and diamonds in the Douglas Creek district of Wyoming |

I spent years in Wyoming. For vacations, I worked for various companies searching for mineral deposits around North America. I left only because the director turned out to be as crooked as Biden and violated rights to free speech, and opening harassed the members of the staff who would not support his corrupt methods. Even though a 3-inch thick document filled with complaints was filed with the AG, Governor, and director (democrats) by the Wyoming Employees Union, we were told all three didn't even bother to open the documents and filed them in the garbage can in front of the representative. It is amazing how corrupt politicians are at every level of government.

|

| Award for a giant gold discovery in Alaska |

But, since I am familiar with Wyoming, let's first talk about the land of Cowboys and Cowgirls. Wyoming has a large variety of minerals and rocks and was a place where new discoveries were made every year from 1977 to 2006. But since 2006, its been quiet. Why?

Not so long ago, diamonds were accidentally found (1975) south of Laramie - a couple of tiny micro-diamonds that required a microscope to see. Since that accidental discovery in Wyoming, many more deposits were found in Colorado, Kansas, Michigan, Montana and Wyoming, and some of the richest diamond deposits in the world were found in Canada, by the early Colorado and Wyoming diamond explorers. If it wasn't for that one discovery in Wyoming, Canada would most likely not be a major diamond producer presently. In Arkansas, diamonds were already known to occur in a olivine lamproite at the Crater of Diamonds State Park.

Using traditional prospecting methods to search for other diamond deposits, some companies and the WGS identified hundreds of mineral anomalies. Such anomalies are typically found by panning for diamond-indicator minerals: rare gemmy minerals caught up in rare volcanic eruptions that accidentally trapped diamond-bearing rock at depths of 90 to 120 miles or more, and carried it to the surface of the earth. One of the more prominent diamond-bearing volcanic rocks is known as kimberlite. Such rocks were identified in South Africa and named after the Kimberly region. Kimberlite is now known as the principal host rock for commercial diamond deposits.

So, while you are prospecting, as soon as you find some kimberlitic indicator minerals by panning in streams or in anthills, you should simply follow the anomaly upstream or upslope until you run out of indicator minerals. At that point, look for some kind of anomaly that may be a depression, a vegetation anomaly, etc. While mapping and prospecting in known kimberlite and diamond fields (such as Iron Mountain, Middle Sybille Creek, State Line and elsewhere), we found kimberlite by searching depressions, vegetation anomalies, carbonate-rich blue-ground soils (reacts to weak hydrochloric acid) in granitic and gneissic terrains, geophysical anomalies, and by following structural alignments of known kimberlites.

Following alignments was one of the easier ways to find kimberlite. Kimberlites erupt along linear fractures and at certain points along these deep fractures, they reach the surface. So, if you can figure out the direction of one of these lineaments, just follow the compass direction keeping your eyes open for something out of place.

|

| Distinct depression near the Kelsey Lake diamond mine in Colorado. There is also a vegetation anomaly associated with this kimberlite pipe (higher stands of grass) known as the Maxwell kimberlite. |

Many of the diamond discoveries in North America (with the exception of the Arkansas pipe) can be attributed to the optimism expressed by Dr. Daniel N. Miller (RIP), who was the State Geologist and Director of the Wyoming Geological Survey (WGS) at the University of Wyoming. Dr. Miller along with a couple of prospectors named Frank Yaussi, and Paul Boden, were about the only people who felt there were possibilities that some kimberlite pipes in Wyoming and Colorado had more than just micro-diamonds.

While searching for gold in Colorado near the Sloan diamond-rich kimberlites, Frank found many diamonds in his gold sluice, but no one at Colorado State University or the University of Wyoming would give him the time of day - they just ignored him (Frank Yaussi, personal communication, 1980). Then Paul Boden from Saratoga, Wyoming found a couple of excellent octahedral diamonds in the Medicine Bow Mountains: again, no one at the University of Wyoming showed any interest (Paul Boden, personal communication, 1977).

|

| The Boden diamonds from the Medicine Bow Mountains, Wyoming |

But Dr. Dan Miller was optimistic and jump-started the diamond industry in North America. He provided some funding to his Minerals Section at the WGS to begin to evaluate the Wyoming deposits, and soon attracted me to his staff, along with two mining companies - Cominco American and Superior Minerals to search for diamonds in the Colorado-Wyoming State Line district. Superior Minerals, with company CEO, Hugo Dummet, tested for diamonds at the Sloan 1 and 2 kimberlites in Colorado, while Cominco tested some Wyoming kimberlites after building a diamond mill at the north end of Fort Collins along highway 287. Years later, Hugo was appointed head of BHP and invested in the great Ekati diamond deposit in Canada, with its 156 diamondiferous kimberlite pipes! After the Ekati discovery, many other diamond deposits were found in Canada - but US exploration, more or less died and most everyone overlooked the Kelsey Lake kimberlites in Colorado.

|

| Look at this anomaly at Iron Mountain! The grass grows greener (and taller) over the kimberlite dike after a spring rainfall (photo by the author). |

|

| Sample of Chicken Park kimberlite, Colorado |

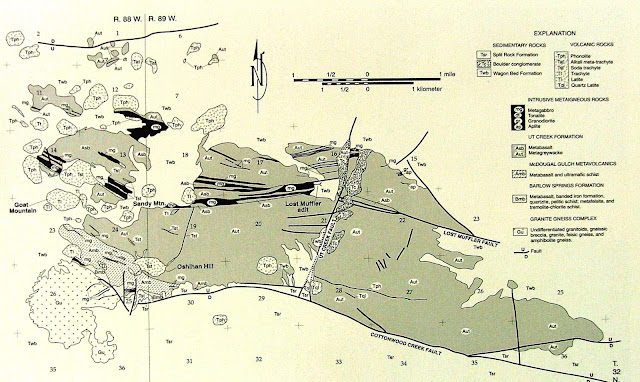

Gold in the Rattlesnake Hills, Wyoming

One impressive gold discovery made in Wyoming in the 20th century was discovery of whole new gold district west of Casper in the Rattlesnake Hills in 1981 with nearby discoveries made a short time later by American Copper and Nickel company. Following my discovery, mining companies and private consultants explored the district and discovered other gold anomalies that led to drilling a significant, large-tonnage, low-grade gold resource at Sandy Mountain. There now appears to be more than 1 million ounces drilled at that site. But, without question, there is more to be found in that district.

What makes this area so significant is the presence of a Archean greenstone belt fragment. 'Greenstone belts' have been equated to 'Gold belts' in some cratons in the world, such as those in Africa, Australia and Canada. Greenstone belt rocks are mostly anomalous in gold; thus, if there is a way to mobilize the gold by hot hydrothermal fluids and geological methods for concentrating the precious metal in chemically favorable rocks or traps (ore shoots) developed during structural deformation, there is a possibility of forming significant to major gold deposits. So, here we have part of an exposed greenstone belt in the Rattlesnake Hills that is more than 2.5 billion years old. It's been intruded by several, much younger, Tertiary age (65 to 2.6 million years old) igneous intrusives that provided heat and mobilized gold and fluids from the intruded rocks. The belt is highly fragmented by deformation during the Laramide orogeny, so, all of the necessary requirements for a major gold deposit are there. I put these ideas together in 1981 after sampling another significant gold deposit in the Seminoe Mountains earlier in 1981 where I found specimens with visible gold, received some highly anomalous assays including a mine dump sample that assayed 2.87 opt Au, and a banded iron formation sample with more than 1.0 opt Au. This area in the Seminoe Mountains also had distinct alteration zones from hydrothermal fluids. It is hard to believe, but I found most of these deposits and dozens of other gold anomalies prior to 1985 with an assay budget of only $100/year! As a comparison, mining companies typically spend hundreds of thousands and even millions on sampling, assaying, and drilling. Just take a look at Oak Island - and that's not even a mining company. And the company the WGS originally contracted to run assays, typically charged about $30/sample. Its a miracle we found anything with that kind of budget.

What makes this area so significant is the presence of a Archean greenstone belt fragment. 'Greenstone belts' have been equated to 'Gold belts' in some cratons in the world, such as those in Africa, Australia and Canada. Greenstone belt rocks are mostly anomalous in gold; thus, if there is a way to mobilize the gold by hot hydrothermal fluids and geological methods for concentrating the precious metal in chemically favorable rocks or traps (ore shoots) developed during structural deformation, there is a possibility of forming significant to major gold deposits. So, here we have part of an exposed greenstone belt in the Rattlesnake Hills that is more than 2.5 billion years old. It's been intruded by several, much younger, Tertiary age (65 to 2.6 million years old) igneous intrusives that provided heat and mobilized gold and fluids from the intruded rocks. The belt is highly fragmented by deformation during the Laramide orogeny, so, all of the necessary requirements for a major gold deposit are there. I put these ideas together in 1981 after sampling another significant gold deposit in the Seminoe Mountains earlier in 1981 where I found specimens with visible gold, received some highly anomalous assays including a mine dump sample that assayed 2.87 opt Au, and a banded iron formation sample with more than 1.0 opt Au. This area in the Seminoe Mountains also had distinct alteration zones from hydrothermal fluids. It is hard to believe, but I found most of these deposits and dozens of other gold anomalies prior to 1985 with an assay budget of only $100/year! As a comparison, mining companies typically spend hundreds of thousands and even millions on sampling, assaying, and drilling. Just take a look at Oak Island - and that's not even a mining company. And the company the WGS originally contracted to run assays, typically charged about $30/sample. Its a miracle we found anything with that kind of budget.

Gold at South Pass, Wyoming

Several other discoveries were made by the WGS during mapping projects in the historic mining districts at South Pass (Hausel, 1991), Seminoe Mountains (Hausel, 1994), Sierra Madre (Hausel, 1986), Laramie Mountains (Hausel and Hausel, 2011) and Medicine Bow Mountains (Hausel, 1989, 1993). In addition to these lode discoveries, prospectors and treasure hunters found many gold nuggets with metal detectors. For example, a 7.5 ounce nugget was found at South Pass by a Wyoming prospector. Another treasure hunter from Ft. Collins found more than 100 nuggets at South Pass, and a prospector from Arizona recovered 399 nuggets in the Sierra Madre (Hausel and Sutherland, 2000).

Several other discoveries were made by the WGS during mapping projects in the historic mining districts at South Pass (Hausel, 1991), Seminoe Mountains (Hausel, 1994), Sierra Madre (Hausel, 1986), Laramie Mountains (Hausel and Hausel, 2011) and Medicine Bow Mountains (Hausel, 1989, 1993). In addition to these lode discoveries, prospectors and treasure hunters found many gold nuggets with metal detectors. For example, a 7.5 ounce nugget was found at South Pass by a Wyoming prospector. Another treasure hunter from Ft. Collins found more than 100 nuggets at South Pass, and a prospector from Arizona recovered 399 nuggets in the Sierra Madre (Hausel and Sutherland, 2000).

I spent 5 summers mapping South Pass. Much of the 1,000 square kilometer belt was unmapped and large parts were unexplored prior to this work. So, over 5 years, I mapped the greenstone belt and all accessible underground mines, and sampled the gold-bearing shear zones. I discovered more than 100 gold anomalies in the region and identified significant gold at a few localities. At the Carissa mine, I found a significant low-grade gold anomaly that suggests there is potential for a million ounce plus gold deposit that extends into the wall rock from the mine and to depths of a thousand or more feet. There is potentially a mineralized zone that could be 1,000 feet wide, 1,000 feet long, and at least 930 feet deep, but is likely more than a few thousand feet deep. In other words, this one deposit likely holds 1 to 3 million ounces. Many gold deposits I identified in the South Pass region were found simply by connecting dots. This is a very important prospecting method!

Most gold deposits at South Pass (and also in other regions of the world) occur in faults, shear zones (a specific type of fault) and quartz veins. These can be visualized as a thin sheet of rock that may be a few feet or more wide, but continue to great depth and can be often followed on the surface for a few hundred to a few thousand feet. In places like South Pass, there are hundreds of prospect pits (gopher holes) dug by prospectors in the past, and many of these line up along the gold-bearing shear zones. In between each of these, gold-bearing shear zones and veins are present, but usually hidden under vegetation or a couple of inches or feet of dirt. Prospecting along such zones always leads to additional gold discoveries in known gold districts! Just take a look at South Pass on Google Earth and you will see hundreds of these old prospects, gopher holes and mines, all pretty much lining up. When I mapped South Pass, I did not have access to Google Earth, so I relied on walking along trends searching for gold, and borrowing whatever aerial photos I could from the US Bureau of Land Management.

Other discoveries

Besides gold and diamonds, other metals and gemstones occur in Wyoming. In 1995, a significant platinum, palladium and nickel anomaly with associated copper silver, gold and silver in the Puzzler Hill area of the Sierra Madre near Saratoga (Hausel, 1997; 2000).

|

| A 7.5 ounce gold nugget found by prospector at South Pass. |

Other discoveries

Besides gold and diamonds, other metals and gemstones occur in Wyoming. In 1995, a significant platinum, palladium and nickel anomaly with associated copper silver, gold and silver in the Puzzler Hill area of the Sierra Madre near Saratoga (Hausel, 1997; 2000).

Wyoming was known for its spectacular jade finds in the 1930s and 1950s, but in recent years, other gemstones were discovered in Wyoming and elsewhere. One of these is a beautiful, 1- to 2-foot long aquamarine from Anderson Ridge found by a prospector from Lander. In 1998, gem-quality peridot was found in the Leucite Hills near Rock Springs. More than 13,000 carats of gem-quality peridot were recovered from two anthills near Black Rock in the Leucite Hills. Other gem-quality peridot occurs in Arizona, Hawaii, and New Mexico. The Wyoming peridot was found because I was searching for peridot in lamproite. The Leucite Hills enclose several lamproite volcanoes and flows, and similar lamproites in Australia at Argyle and Ellendale contain diamonds - but only those lamproites that have olivine (peridot).

Another attractive gem discovered in 1998 in Wyoming is referred to as iolite, also known as cordierite and water sapphire. This led to a world-class discovery, first with spectacular iolites I found at Palmer Canyon, then with some iolite gemstones that potentially weigh more than a ton, at Grizzly Creek. But then I was able to find gem-quality iolite also at the Sherman Hills in the Laramie Mountains. This latter site is mostly unexplored, but based on trenching of cordierite around world war II, this latter Sherman Hills-Raggedtop deposit could host more than a trillion carats of the gemstone! The gem, known as iolite (gem-quality cordierite), is transparent, violet to deep blue (Hausel and Sutherland, 2000; Hausel, 2014). I found the easiest way to search for iolite is to look for areas that contain aluminum-rich (amphibolite-grade) metamorphic rocks such as kyanite schists, cordierite schists and andalusite schists and then start looking for some attractive glassy gemstones that are blue to purple in color.

|

| Rhodolite (pyrope garnet) faceted from rough material collected in the Green River Basin of Wyoming. |

Rubies and sapphires also occur in places like Montana, North Carolina and Wyoming. I found at least 5 ruby deposits in Wyoming simply by searching for a rock type known as vermiculite schist. In Europe, this rock is sometimes referred to as glimmerite. It is a mica rich rock that has more than enough aluminum to produced ruby or sapphire (both aluminum-oxides) if the right conditions were met during the past - which I discussed in my 2014 book on gemstones. Another beautiful gemstone is benitoite - found in California - it looks just like sapphire. While working for a company searching for diamonds in California, I discovered a new occurrence of benitoite. The samples recovered from the area had many, very attractive benitoite gems. Earlier, while searching for diamonds further north, I found serpentines filled with chromian diopside (sometimes referred to as Cape Emerald. But, while prospecting for kimberlite and lamproite in Colorado and Wyoming, I found many of the chromian diopsides and chromian enstatites were spectacular gemstones that put most emeralds to shame.

If you are a fan of the Curse of Oak Island, an old, faceted, rhodolite gemstone was discovered while using a metal detector. Rhodolites are pyrope garnets, and these are found in Alaska, Arizona, northern Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, Kansas, Michigan, and even the Uinta Mountains, Utah. Beautiful rhodolites are often associated with kimberlite - and many are found in anthills in areas where there are kimberlites and lamprophyres.

So kick around a few rocks, and keep your eyes open, and you may find a new mineral deposit or occurrence, maybe even a whole new district.

History of Prospecting

Wyoming was first prospected for gold. Gold may have initially been found by Spaniards more than 200 years ago. However, history records that gold was discovered later in 1842. According to these reports, fur trappers found gold in streams in the Wind River country in a part of the Northwest Territory that would later become Wyoming. Several years later, in 1863, immigrants passing near the Oregon Buttes along the Oregon Trail to the south reported finding gold near the trail. Four years later, after the region had been made part of the Dakota Territory, prospectors working further north discovered a rich lode along Willow Creek at the base of the Wind River Mountains. This led to the sinking of the Carissa shaft. South Pass City was built within site of the gold mine.

Hundreds of prospectors rushed to South Pass. Reports vary, but between 2,000 to 10,000 gold seekers may have populated the South Pass area at the peak of the rush. Gold was soon discovered in several nearby lodes and placers in the region, and a few other towns rose from the dust. Hamilton City (near Miners Delight) and Atlantic City reported populations of 1,500 and 500 people, respectively. Pacific City to the south claimed a population of 600. A few years later, after the region became part of the Wyoming Territory, gold discovered on Strawberry Creek led to the establishment of a town named Lewis Town, which later became known as Lewiston. Soon Wyoming recorded many other gold discoveries in the Seminoe Mountains, the Medicine Bow Mountains, the Sierra Madre and in the Black Hills. Gold has been found in every mountain range in the state, and many streams draining the mountains also contain gold. In fact, during a recent research investigation of placer deposits, the Wyoming State Geological Survey found gold in many streams draining the northern Medicine Bow Mountains. Gold was even found gold in an ancient stream channel in the Laramie City dump! So you never no where you might find gold.

Gold was king until near the end of the 19th Century, when the price of copper rose high enough that it was also considered a precious metal. The nation needed copper, and rushes to the Absaroka Mountains, Sierra Madre, Medicine Bow Mountains, Owl Creek Mountains, and Laramie Range brought many people to Wyoming. The greatest copper mine in Wyoming, the Ferris-Haggarty mine in the Sierra Madre, was discovered on a cupriferous gossan. To recover the rich ore, a 16.25-mile long aerial tramway was constructed to haul ore from over the continental divide from the mine on the west side of the range, to the Boston-Wyoming mill and smelter complex at the town of Riverside on the east side of the range. The copper boom was followed by many other discoveries including platinum, palladium, asbestos, manganese, titanium, uranium, iron ore, coal, trona, bentonite, oil, gas, jade, and many other mineral commodities.

Mining and prospecting are important to Wyoming, and the State reaps tremendous profit from the taxation of the State’s mineral resources. We hope you enjoy our state and have a successful time hunting rocks and prospecting for gold. When you find the mother lode, you will want to stake a claim.

Mining Claims & Leases

If you make a discovery while prospecting or rock hunting, the type and size of Federal mining claims are the same in every state, as designated by Congress. Four types of mining claims can be staked on multiple-use ‘public’ lands: (1) lode claims, (2) placer claims, (3) tunnel claims, and (4) mill site claims. The most common claims are lode and placer claims.

A lode claim is reserved for mineralized veins or on any high-value mineral or rock occurring in place, such as gold-bearing veins found in many mountains in Wyoming, or diamond-bearing kimberlites found in the southern Laramie Range. This also includes disseminated mineralized deposits such as the porphyry copper deposits in the Absaroka Mountains and roll-front uranium deposits in many Wyoming basins.

Placer claims are staked on detrital mineral deposits formed by the concentration of valuable minerals from weathered debris. The most common placer deposits are those found in active streams in river gravels such as on the Sweetwater River and Rock Creek in the Atlantic City-South Pass mining districts on the southeastern flank of the Wind River Mountains, where gold was originally found in 1842.

The size of a lode claim is limited to a maximum of 1500 feet in length by 600 feet wide. If a lode claim is staked on a vein, the vein should divide the claim in half, with approximately 300 feet on either side of the vein. A discovery notice is required to be posted on the point of discovery. The claim notice should contain information about the claim including the name of the claim, the discoverer and locator, the date of discovery, the length of the claim along the vein measured each way from the center of the discovery shaft or point, the general course of the vein, and a description of the claim by reference to natural or fixed objects. If the land is surveyed, a description by reference to section or quarter section corners should be noted. Six monuments or posts are required to mark the outline of the claim in Wyoming. The four-corners and the center of each side line is marked. One side of each monument is marked to indicate which side of the monument faces the claim.

For additional information concerning staking claims check with the US Bureau of Land Management. After you make a discovery and mark it with a notice, you have 60 days to file your discovery with the County Clerk, and 90 days to file the claim with the U.S. Bureau of Land Management.

A placer claim typically covers 20 acres, and is located by legal subdivision giving quarter sections, township, and range. If your discovery is on unsurveyed land, it is located by reference to a natural or fixed object. Larger placer claims can be located by an association of locators, and these are limited to 160 acres for a total of eight locators, or a maximum of 20 acres per individual in the association.

The claim is marked with a securely fixed notice or sign containing the name of the claim (you must designate the claim as a placer claim, such as the Mega-nugget Placer), the name of the locator or locators, the discovery date, the number of feet or acres claimed, and a description of the claim with reference to fixed or natural objects. All four-corners of the placer claim are required to be marked by substantial monuments or posts. Then you have 90 days to file a certificate of discovery with the County Clerk and Bureau of Land Management after you have made your discovery.

Information on mill site and tunnel site claims can be obtained through the U.S. Bureau of land Management. If you are interested in specific information on staking mining claims in Wyoming, a reference is the Mineral and Mining Laws of Wyoming published by the Wyoming Geological Survey. If you make a discovery on State Land, you will need to apply for a lease from the Department of Lands in Cheyenne.

WHAT TO LOOK FOR

Some general localities are described below to get you started on prospecting, and a select reading list is provided on the last page. A good addition to the reading list would be a descriptive rock and mineral reference book to help you identify some of the mere difficult minerals.

Agates, Jasper, Petrified Wood

Agate, jasper, and petrified wood are forms of chalcedony. Chalcedony is a compact, or massive form of silica. Commonly, it forms by precipitation of silica-rich solutions as veins, as cavity linings, or by replacement in a wide variety of rock types.

By definition, agate imparts a distinct color banding resulting from impurities trapped in the silica as it crystallizes, and petrified wood results when the original woody material is replaced by silica-rich solutions, usually during rapid burial by silica-rich volcanic ash. Jasper, is a brightly colored (red, brown, yellow) form of chalcedony.

Several distinctive varieties of chalcedony found in Wyoming are given descriptive or geographical names by rock hunters. Some are so distinctive that many rock hounds can give you the geographical location within in a few miles of where the sample was collected by merely looking at a hand-size sample.

Banded & Moss Agate. Varieties of banded agate include Rainbow agate, which diffracts light into a rainbow spectrum of colors when thinly sliced. Rainbow agate is found in the Wiggins Formation in the southern region of the Absaroka Mountains near Yellowstone, and in gravels along the Wind River north of Riverton. A red and white banded agate known as Dryhead agate is found along the Bighorn River northeast of Lovell and in sediments eroded from the Hartville uplift northeast of Guernsey.

|

| Youngite agate breccia |

Moss agates have a distinct dendritic pattern from iron oxide or manganese oxide in white to blue chalcedony. A distinct agate known as Sweetwater agate contains manganese oxide dendrites in dark blue to dark gray-blue chalcedony. Sweetwater agates are found along the Sweetwater River and Sage Hen Creek west and northeast of Jeffrey City, respectively.

|

| Blue forest agate (courtesy of Wayne Sutherland |

|

| Goniobasis agate |

Jasper. Jasper is reddish to tawny chalcedony, and is mineralogically and chemically identical to agate, with the exception of trace metals which impart the reddish to tawny color. Many jaspers have been found in the state, but some of the better known localities are in the Granite Mountains in central Wyoming. Two extraordinary localities occur in the Tin Cup and the Rattlesnake Hills districts.

Copper

Deep green to blue stains on many rocks on old mine dumps may be copper carbonates known as malachite and azurite. A bronze colored metallic mineral with a patina of purple and blue, known as chalcopyrite, is a common copper mineral in many of Wyoming’s historic mining districts. When the copper deposits weather, they often produce a copper-stained gossan that is a good place to look for visible gold. Some gossans cap copper-enriched zones at shallow depths where the water table is encountered. Gold, silver, lead, zinc and molybdenum may be found in association with copper.

About 30 million pounds of copper were mined in Wyoming’s past. Most of the production was from the Encampment District in the Sierra Madre, where several mines were developed to support the Boston-Wyoming smelter and mill complex at Riverside. One of the more famous was the Ferris-Haggarty. Ore from this mine was shipped from the mine site along Haggarty Creek in a 16.25-mile long aerial tramway. The tram ran from the mine, up the western slope and over the continental divide of the Sierra Madre, and down the eastern slope to a mill at Riverside. Some high-grade ore from the mine was incredibly rich containing 30 to 40% copper. For comparison, some of the major modern copper mines of today produce ore that has only 0.7% copper.

|

| Copper ore, Ferris-Haggarty mine |

Chalcopyrite (copper-iron-sulfide) is a brassy-orange, brittle, metallic mineral that weathers to limonite and a variety of copper minerals including malachite, black tenorite, and earthy red cuprite.

Malachite, a light- to dark-green copper carbonate, will react with dilute (10%), hydrochloric acid (Muranic acid, a very weak form hydrochloric acid, will also work).

by emitting bubbles of carbon dioxide, similar to the fizz in soda pop. If you place the same acid on tenorite or cuprite; you will find a thin plate of native copper will replace a well-used rock hammer after rubbing the hammer into the acid.

Diamonds

|

| Schematic cross-section of a classical kimberlite pipe and feeder dike complex |

The first diamond pipe was found in Wyoming in 1960; but, the diamonds themselves were not discovered until 1975. Since then, more than 130,000 diamonds have been mined in a region south of Laramie extending from Tie Siding, Wyoming to Prairie Divide, Colorado. A large percentage of the diamonds that have been mined have been high-quality gemstones. A few diamonds larger than 28 carats have been recovered from the Kelsey Lake diamond mine along the Colorado-Wyoming border. The largest known diamond found in Wyoming weighed more than 6 carats.

|

| Kelsey Lake diamond mine - photo by W. Dan Hausel |

Jade

Jade is the gemologist's designation applied to two distinct and unrelated mineral species: nephrite and jadeite. Of the two gemstones, only nephrite has been found in Wyoming. But it has been found in such abundance that nephrite jade is often considered synonymous with "Wyoming Jade", even though it is found elsewhere in the world.

Nephrite is an amphibole formed of extremely dense and compact fibrous tremolite-actinolite. Nephrite and jadeite are indistinguishable in hand specimen, and require x-ray diffraction analysis to identify.

|

| Wyoming jade (nephrite) with quartz crystals |

Nephrite jade is extremely tough and resistant to fracturing. As a result, rounded boulders of nephrite are nearly impossible to break with a hammer. Because of toughness and attractive appearance, nephrite, which has been termed the "axe stone", has been prized since prehistoric times.

Only carbonado, a black granular to compact industrial form of diamond is tougher than jade. However, gem-quality diamond, the hardest known mineral found in nature, lacks the toughness of jade and is easily smashed with a hammer. It is the toughness of jade, combined with its hardness that makes the gemstone carvable and durable.

Its hardness, ranges from 6 to 6.5 (or about the same hardness as a steel file). The green color in nephrite jade is the result of iron within the crystal lattice. When iron is absent, the mineral is practically colorless to cloudy white, resulting in a variety known as ‘muttonfat jade’. Other colors also depend on the abundance of iron in the crystal lattice, and these include translucent, emerald-green ‘imperial jade’; ‘apple-green’ jade, ‘olive-green’ jade, ‘leaf-green‘ jade, ‘black‘ jade, and ‘snowflake’ (mottled) jade (Bauer, 1968). The greater commercial values are attached to the lighter green, translucent varieties.

Deposits of nephrite jade are accompanied by distinct alteration mineral assemblage that can be used to help locate hidden jade deposits. Where found, the jade is accompanied a distinct, mottled pink and white granite-gneiss with secondary green clinozoisite, pink zoisite, pistachio green epidote, green chlorite, as well as white plagioclase which is pervasively altered to white mica.

When found, jade may be covered with a cream to reddish-brown weathered rind. But when naturally polished with a high-gloss waxy surface, known as 'slicks', the jade is usually recognizable.

Large volumes of jade were found in central Wyoming a few decades ago. Jade has been reported as far west as the Wind River Mountains (McFall, 1976), and as far east as Gurnsey and the Laramie Mountains. To the north, it has been reported in the Wind River Basin, and has been found as far south as the Rawlins golf course near Interstate 80 (Hagner, 1945) and further south in the Sage Creek Basin near the Sierra Madre Mountains.

Sapphire and Ruby

Sapphire and ruby are gem varieties of corundum. Corundum the second hardest known naturally occurring mineral, can be recognized because it will only be scratched by diamond, and is usually found as hexagonal prisms with distinct rhombohedral cleavage.

The deep red variety of corundum is termed ruby. All other colors of gem-quality corundum are known as sapphires – thus sapphire can be blue, green, pink, yellow and white. Some rare varieties of corundum may contain small mineral inclusions of rutile aligned in specific, crystallographic directions forming three lines oriented 120° to one another. These will produce a star effect when light if reflected from the mineral, and are known as star rubies, or star sapphires.

Gem quality sapphires and rubies are rare in Wyoming; however, a few crystals (including star rubies) have been reported from in the Granite Mountains north of Jeffrey City. Other rubies and sapphires have been found in the Palmer Canyon area of the Laramie Mountains west of Wheatland.

Gold.

Gold occurs as a heavy, malleable, warm colored metal. When scratched with a knife, the yellow flake or nugget will have a distinct gold-colored indentation. Gold is also very heavy, and is 15 to 19 times heavier than water. For comparison, quartz is only about 2.8 to 2.9 times heavier than water.

I

n lodes, gold is often found with sulfide minerals. These may include pyrite (iron-sulfide), also known as fool's gold, arsenopyrite (iron-arsenic-sulfide), and chalcopyrite (copper-iron-sulfide). Pyrite can fool many people. It is often mistaken for gold; however, pyrite is much lighter and forms brass-colored, brittle crystals that often have cubic (6-sided) or pyritohedral (12-sided) habit. Unlike gold, pyrite is not malleable and can be easily crushed to a dark greenish-grey powder by striking the mineral with a rock hammer. Scratching a streak plate (a rough, white piece of tile) with pyrite will also leave a distinct black streak of powder on the tile.

|

| Gold from South Pass. Photo by W. Dan Hausel |

But pyrite sometimes contains hidden gold within its crystal structure - it can hide as much as 2,000 parts per million gold (this would be equivalent to a ton of pyrite containing about 60 ounces of gold). The gold in the pyrite would not be visible, unless some the mineral had oxidized and was replaced by limonite (a hydrated iron-oxide that is essentially rust) producing what is known as gossan, or boxworks.

A gossan is essentially a reddish- to yellowish-brown, iron-rich mass found in some veins and faults. Gossans provide excellent places to search for gold, since limonite produced by the oxidation of gold-bearing pyrite, may contain specs, rods, or masses of visible gold. The better places to look for visible gold in gossans are in web-like, honeycomb, vuggy zones known as boxworks. Boxworks result from oxidation and removal of the pyrite, leaving behind silicified ridges, or outlines of the former crystals. Gold, however, being relatively inert, will remain in place, and can sometimes be found on the boxwork ridges.

Other sulfides found with gold include arsenopyrite and chalcopyite. Arsenopyrite, a brittle, silver-metallic, mineral, will oxidize to a greenish-yellow limonite known as scorodite. When arsenopyrite is struck with a rock hammer, a garlic odor will be detected. This is due to arsenic in the sulfide. Some arsenopyrite can potentially hide as much as 1,000 ppm gold in its crystal lattice.

In general, gold is found in lodes and placers. The term 'lode' simply describes an in situ mineralized vein or fault as opposed to a placer, which consists of reworked, detrital, heavy minerals concentrated in active or inactive stream gravels. Veins generally form narrow sheets of quartz, whereas most faults consist of vertical to near vertical sheets of intensely deformed rock that often contain quartz veinlets and boudins (lenses). When mineralized, the gold values in lodes are typically erratic along much of the length of the structure and random sampling may yield only trace amounts of gold. However, periodic ore shoots (enriched zones) are sometimes encountered. Some of these pockets may average more than 1 ounce of gold per ton (Hausel, 1999b). At such high grades, the gold will often be visible to the naked eye and individual pieces of rock may produce specimen-grade samples, especially when ore grades run higher than 1 ounce per ton.

Gold has been found in all of Wyoming’s mountain ranges as lode and/or placer deposits. Some of the better places to search for gold include the Wind River, Seminoe Mountains, Medicine Bow Mountains, Mineral Hill, and Sierra Madre.

South Pass District. The best place to search for specimen grade gold samples in Wyoming is the South Pass district, along the southeastern margin of the Wind River Mountains. The district encloses several gold-bearing faults (shear zones) and some veins. Many of these are located on maps published by the Wyoming State Geological Survey, and there thousands of feet of gold-bearing shears in this region that have never been seriously prospected!

This area is also a good place to search for specimen-grade samples. For example, some ore recovered from the Carissa mine in 1908, assayed as high as 260 ounces per ton gold (Hausel, 1999c). The Miners Delight mine at South Pass was also a fairly good source of gold. Downslope from the mine, historical reports indicate that water was pumped from the shaft and used to mine Spring Gulch. Several 1 and 2 ounce nuggets were found in the gravels including one 6 ounce nugget. One lump of specimen-grade quartz was found in 1873 that was as large as a water bucket. According to one witness, it looked as if it contained a pound of gold. In nearby Yankee Gulch, northeast of the Miners Delight mine, 8 to 15 ounces of gold were mined per day including one nugget that weighed nearly 5 ounces (Hausel, 2001).

In the central part of the district, the Rock Creek placer produced one fist-size chunk of quartz filled with an estimated 24 ounces of gold. A boulder found nearby in 1905, contained an estimated 630 ounces of gold!

|

| The author (GemHunter) stands in middle of photo at the base of Zirkel Mesa in the Leucite Hills wearing white field hat. |

West of the Mint-Gold Leaf lode is a short drainage known as Giblin Gulch. The gulch cuts across the western end of the Mint-Gold Leaf shear zone, and drains into Strawberry Creek. In 1932, several nuggets were found in the gulch including some that weighed 5.2 and 5.3 ounces. Other nuggets found in this area included two that weighed 3 and 4.5 ounces. These were found in Two Johns Gulch in 1905. Another report indicated that five 'good-size' nuggets were found in the Big Nugget placer in 1944. The locations of the Big Nugget and Two Johns gulches are unknown, but possibly these are the same as Giblin gulch.

|

| Gold from Douglas Creek, photo by W. Dan Hausel |

Gold Hill district: To the north of Douglas Creek, is the Gold Hill district. Some pecimen-grade samples have also been reported in this district in the Medicine Bow Mountains. Samples collected from the Acme mine in the past reportedly assayed as high as 2,100 opt! Specimen-grade samples from the nearby Mohawk mine reportedly assayed as high as 1,450 opt!

Seminoe Mountains district. The Seminoe Mountains lie near the central part of the state northeast of the town of Rawlins and north of Sinclair. On Bradley Peak, at the western end of the range, a small group of mines were dug on narrow quartz veins. Several specimen-grade samples of gold-bearing quartz were found on the mine dumps by the author in 1981 (Hausel, 1994). Deweese Creek, which drains the Penn mines, shows very little evidence of placer mining. But based on the number of samples found with visible gold on the mine dumps, this creek probably contains some gold.

Platinum

Platinum-group metals are closely associated with ultramafic rocks with high magnesium content, particularly those that are enriched in olivine, such as peridotites. A peridotite is a dark-greenish rock composed almost entirely of olivine with lesser pyroxene. Peridotites alter to serpentine, thus when prospecting for platinum, the prospector should investigate rocks described as ultramafic, peridotite, or serpentinite.

Platinum and palladium may be found in nuggets, grains, and flakes, and in certain sulfide minerals such as sperrylite (palladium sulfide), or may occur as impurities in some copper-sulfide minerals such as covellite.

Platinum-group metals have been mined from peridotites, nickel-copper-deposits in alkaline igneous rocks and in thick gabbros. However, the major platinum-group metal deposits are found in layered, mafic complexes such as the Bushveld complex, South Africa, and the Stillwater complex, Montana.

Platinum-group metals have been found in both placers and lodes in Wyoming. Platinum found in the Douglas Creek district occurs as grains or flakes. Platinum in nature has a specific gravity in the range of 14 to 17. One common impurity is iron: when in sufficient amounts, it may cause the platinum to be weakly magnetic. Platinum is a malleable, tough, bluish-gray (steel-colored) metal. It has a very high melting point, and is not affected by an ordinary blowtorch. It has a hardness of 4 to 4.5, and produces a shining silver streak when scratched by a knife.

Platinum and palladium may occur as impurities in gold, producing what is known as white gold. This has a similar appearance to amalgamated gold. But unlike most amalgamated gold, white gold will have a consistent color throughout the metal. Whereas amalgamated gold may only have a bright silver rind produced by mercury, that is distinctly gold-colored on the interior of a nugget.

Some of the better anomalies have been identified in the in the Medicine Bow Mountains in Lake Owen and Mullen Creek layered complexes, and the Centennial Ridge district, and in the Puzzler Hill area of the Sierra Madre to the west.

The New Rambler mine, located along the northeastern edge of the Mullen Creek complex, was one of the only known mines in North America that produced platinum and palladium during the early 1900s. A cupriferous gossan was discovered here near the turn of the 19th century. A shaft, known as the New Rambler shaft, was sunk on the gossan. Ore from the mine included many copper minerals including platinum-bearing covellite (CuS) and chalcocite (Cu2S), with some veins containing a rare mineral known as sperrylite (PtAs2). A search of nearby mines resulted in other platinum-group metal discoveries.

REFERENCES CITED

Bauer, M., 1968, Precious Stones, Volume 2: Dover Publications, Inc, New York, p. 261-627.

Hagner, A.F., 1945, Diehl - Branham jade: Wyoming State Geological Survey Mineral Report MR45-7, 2 p.

Hausel, W.D., 1989, The geology of Wyoming's precious metal lode and placer deposits: Geological Survey of Wyoming Bulletin 68, 248 p.

Hausel, W.D., 1991, Economic geology of the South Pass granite-greenstone belt, Wind River Mountains, western Wyoming: Geological Survey of Wyoming Report of Investigations 44, 129 p.

Hausel, W.D., 1993, Guide to the geology, mining districts, and ghost towns of the Medicine Bow Mountains including the Snowy Range scenic highway: Geological Survey of Wyoming, Public Information Circular 32, 53 p.

Hausel, W.D., 1994, Economic geology of the Seminoe Mountains greenstone belt, Carbon County, Wyoming: Geological Survey of Wyoming Report of investigations 50, 31 p.

Hausel, W.D., 1986, Mineral deposits of the Encampment mining district, Sierra Madre, Wyoming-Colorado: Geological Survey of Wyoming Report of Investigations 37, 31 p.

Hausel, W.D., 1996, Economic geology of the Rattlesnake Hills supracrustal belt, Natrona County, Wyoming: Geological Survey of Wyoming Report of Investigations 52, 28 p.

Hausel, W.D., 1997, The geology of Wyoming's copper, lead, zinc, molybdenum, and associated metal deposits in Wyoming: Geological Survey of Wyoming Bulletin 70, 224 p.

Hausel, W.D., 1998, The Rattlesnake Hills - Wyoming’s little known gold district: International California Mining Journal, v. 68, no. 4, p. 44-46.

Hausel, W.D., 1999a, Gold Fever: International California Mining Journal, v. 68, no. 12, p. 17-19.

Hausel, W.D., 1999b, Prospecting ore shoots and hidden veins for specimen-grade gold samples: International California Mining Journal, v. 68, no. 10, p. 7-28.

Hausel, W.D., 1999c, The Carissa Gold Mine, South Pass, Wyoming – A sleeper?: International California Mining Journal, v.68, no. 11, p. 14-16.

Hausel, W.D., 2000a, The Wyoming platinum-palladium-nickel province: geology and mineralization: Wyoming Geological Association Field Conference Guidebook, p. 15-27.

Hausel, W.D., 2000b, The Centennial lode and the Centennial Ridge district, Wyoming: International California Mining Journal, v. 70, no. 2, p. 14-22.

Hausel, W.D., 2000c, Prospecting for platinum in Wyoming: International California Mining Journal vol. 70, no. 4, p. 19-34.

Hausel, W.D., 2001, The South Pass gold placers, western Wyoming: International California Mining Journal, v.70, no. 8, p. 29-35 & 41-42.

Hausel, W.D., and Sutherland, W.M., 2000, Gemstones and other unique minerals and rocks of Wyoming - a field guide for collectors: Wyoming State Geological Survey Bulletin 71, 268 p.

McFall, R.P., 1976, Wyoming jade: Lapidary Journal, v. 30, no. 1, p. 182-194.